"If you’re really serious, dig into saxophonist Javier Arau’s page on Augmented Scale Theory and three- and four-tonic systems, which is on point."

--Peter Hum, Ottawa Citizen

Augmented Scale Theory

Augmented Scale Theory

A theory that helps unite traditional and chromatic jazz improvisation

Exercises

Augmented Scale Theory Exercises are now online! Click here to view exercises.

Welcome from Javier Arau

Welcome to the Augmented Scale Theory page. Augmented Scale Theory can help jazz improvisers play on difficult chord changes, including "Giant Steps," "26-2," and other Coltrane tunes. It also helps with making melodic sense of both bebop and "outside" improvising. The theory serves as an aid to intermediate and advanced improvisers, and I plan on posting practical playing materials and exercises in the near future. Please check back in periodically to view new postings. Both the formal abstract and paper presented here are written with a fairly advanced audience in mind. Please take your time while reading the paper, and let me know how it goes. I have received emails and inquiries from jazz players all over the world, and I look forward to hearing from you, too! I now offer private lessons on Augmented Scale Theory, both online (see above) and through my NYC studio at New York Jazz Academy. If you are interested, feel free to contact me. Also, feel free to try my new, unrelated, sample lessons on basic improvisation.

About the Author

Saxophonist Javier Arau is a four-time Down Beat Magazine award winner and is a leading jazz educator, researcher, and composer. He is a former member of the BMI Jazz Composers Workshop, and his scholarly works and compositions have been published by Jazz Educators Journal, UNC Jazz Press and Dorn Publications. Other honors include national awards from IAJE, ASCAP, MENC, MTNA, and more. Javier studied music theory with George Russell and Robert Cogan, composition and orchestration with Bob Brookmeyer, Jim McNeely, and Lee Hyla, and improvisation with George Garzone, Joe Maneri and Jerry Bergonzi. Javier earned his Master of Music degree from the New England Conservatory in Boston, and he has held formal teaching positions at Lawrence University. Javier founded the widely recognized jazz school New York Jazz Academy, where he currently serves as Program Director. He is based in New York City and give clinics and performances worldwide. Feel free to contact Javier for inquiries.

Javier presented his introductory paper on Augmented Scale Theory at the International Jazz Composers' Symposium in Tampa, FL, on June 14, 2008. Stay tuned for more information on the theory and Javier's research findings.

Paper Abstract

Despite the prevalent use of intervallic cells as source material among modern jazz composers, little research has been published on bridging the divide between the atonal approach of set theory and the more tonal harmonic tendencies of classic jazz. Modern jazz language thrives on diverse harmonic and melodic elements, but jazz lines that deviate from given harmonies still tend to be generalized as being "outside the changes" – an unfortunate description that fails to specify the logic behind complex lines. While tonal hierarchy is typically framed in terms of major and minor tonalities, tonal hierarchy can also be derived through a reexamination of the pitch intervals that comprise the augmented scale. My theoretical research has included extensive study of three-tonic systems (e.g. Coltrane changes), four-tonic systems (tri-tone substitutions, etc.), and historical compositional practices ranging from ancient Greek systems through 20th century techniques. This study concludes that the augmented scale unifies three- and four-tonic systems while also establishing tonal hierarchy in music incorporating elements of set theory. This paper is part of a larger study on augmented scale theory and serves as an introduction to my research on this topic. My intent in researching augmented scale theory is to help the jazz composer and improviser reach creative freedom while approaching Coltrane changes and other challenging chord progressions, to assist in reconciling tonal and atonal structures, and to contribute to future research on jazz and set theory.

Jazz Line and Augmented Scale Theory

Using Intervallic Sets to Unite Three- and Four-Tonic Systems

INTRODUCTION

Contemporary jazz music is experiencing a renaissance of sorts, as the tonal language of early jazz and bebop, deeply rooted in Western harmony and still an influential and governing force in current music, increasingly mingles with a chromatic and atonal palette. Rather than embracing a free-for-all, chromatic and "outside" approach introduced to jazz decades ago, many musicians today increasingly seem to be interested in grounding atonal chromaticism within a tonal system. Current trends in chromaticism seem to have been influenced considerably by a philosophy, espoused by artists such as David Liebman[1] and George Garzone,[2] claiming that a strong harmonic line can hold its own when superimposed over any chord change, however unrelated. Liebman suggests providing balance to such chromatic superimposition by making at least an occasional return to tonal "diatonic lyricism,"[3] and he is absolutely correct when he stresses that experience, not to mention a very aware and developed set of ears, can help the jazz musician find a successful chromatic approach.[4] In fact, the challenge for a musician might not lie in working solely within an atonal system; set theory and other methods of manipulating intervals already have proven to be popular in handling such material. It is often in bridging between atonal and tonal landscapes that problems arise. Chromatic approaches to tonal harmony are becoming so prevalent among jazz artists that a player who adds only an occasional flat-9 or flat-13 on a V chord can sound entirely dated.[5] If chromatic notes like the flat-13 have become so common that they are often preferred to tonal choices such as the 5th of a V chord, then there is a reason for developing a specific theoretical system that embraces chromaticism as a more structural element of jazz harmony, reconciling "inside" and "outside" harmonic development and aiding any musician in the quest to develop a chromatic language within a broader tonal context.

A clear solution to the challenges of moving freely between chomaticism and tonality lies with the augmented scale, a symmetrical pitch collection that successfully unites tonal and atonal systems. This paper, divided into two parts, examines how the augmented scale acts as such a unifying agent. The first part explores the relationship between the 3-tonic system embedded within the augmented scale and the 4-tonic system relating to classic jazz and tonal harmony, surveying how chromatic interval sets within the augmented scale imply harmonies embedded within both systems. The first part also stresses, in particular, the significance of the flatted-6th as the primary bridge between these two systems. The second part introduces a complete chomatic palette structured around the four augmented scales, revealing unifying harmonic and geometrical relationships between them and traditional tonic-dominant harmonies, helping to explain how certain harmonies may be superimposed over one another. What begins, in part one, as a study of the flatted-6th as a common entry point into chromaticism, evolves, in part two, to reveal a complete chromatic system embracing the entire tonal and atonal spectrum. While this paper focuses on jazz line and augmented scale theory, augmented scale theory also has broad implications for use as an aid in theoretical analysis and in musical composition.

PART ONE — The augmented scale and 3- and 4- tonic systems

1.1 A common chromatic landscape: The augmented scale and the 3-tonic system

Principles of set theory can be valuable when generating and developing atonal music.[6] Two common intervallic pitch sets that continue to be prevalent in modern music are the (013) and (014) trichords (see Fig. 1). The (014) is of particular interest here, as it alone generates the augmented scale (Fig. 2), a hexatonic scale comprised of alternating minor second and minor third intervals.

Fig. 1: (013) and (014) trichords

Fig. 2: C augmented scale with embedded (014) trichords

Central to tonal harmony is the tonic-dominant relationship, but an augmented scale is commonly ordered in a way that helps outline its implicit augmented chords (Fig. 3). It also highlights the scale's tendency toward tonal ambiguity, as a clear hierarchical tonal relationship between augmented chords does not exist.

Fig. 3: C augmented scale, highlighting alternating B+ and C+ chords

Deemphasizing the Ab and highlighting the G in the C augmented scale below (Fig. 4) helps illustrate how the augmented scale can hint at a tonal hierarchy, where C major is the tonic I chord and G and B imply a V chord. Now the Ab can be seen as an upper neighbor with a tendency to resolve to the G. The same can be said for B and Eb, as they tend to move to C and E, respectively.

Fig. 4: C augmented scale, highlighting embedded C major tonality

Embedded within the augmented scale are three major triads and three minor triads (Fig. 5). These triads help form a 3-tonic system, most commonly identified with John Coltrane's "Giant Steps" and also explored in countless other compositions in jazz (see Fig. 6 for a sample chord progression). Coltrane's chromatic approach to composition and improvisation continues to influence modern jazz harmony and is integral to understanding augmented scale theory. A 3-tonic system can be viewed geometrically as an equilateral triangle. Its three points represent the three major chord "tonics" (I) and its sides represent their corresponding, implied dominant (V7) harmonies (Fig. 7).

Fig. 5: Embedded major/minor triads within the C augmented scale

Fig. 6: "Coltrane Changes" superimposed over a II-V-I progression (key of C)

Fig. 7: 3-tonic system geometrically represented by an equilateral triangle

1.2 Classic jazz roots: The diminished scale and the 4-tonic system

The 4-tonic system is derived from a fully diminished scale, a symmetrical octatonic scale built upon (013) trichords (Fig. 8). When major triads are built upon scale degrees 1, 3, 5, and 7 of a "whole-half" diminished scale, 4 tonics, separated by minor third intervals may be formed (Fig. 9). II-V chords and II-V chord substitutions, including the tritone substitution and the minor third substitution[7] common to classic jazz, stem from the II-V chords that correspond with each of these four tonics (Fig. 10).[8] These embedded chords make 4-tonic systems essential and relevant to classic jazz and bebop harmony.

Fig. 8: C diminished scale (whole-half), with embedded (013) trichords

Fig. 9: The four tonics, separated by minor thirds

Fig. 10: II-V chord progressions stemming from the four tonics

A 4-tonic system can be viewed geometrically as a square—its four points corresponding to the four tonics—but because each II-V substitution traditionally resolves to the same tonal center, a more helpful illustration keeps a singular tonic and positions the four implied II-V harmonies in the square's four corners (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11: 4-tonic square, with singular tonal center and implied II-V chords

Hear the 4 progressions resolving to a C major tonic, counter-clockwise from bottom left:

1.3 Getting from here to there: Using implied leading tones to bridge 3- and 4-tonic systems

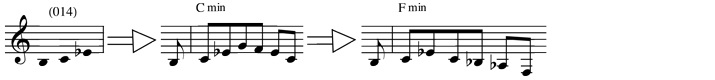

Interval sets within the augmented scale naturally imply specific embedded chords. When the semitones in each (014) trichord are treated as leading tones, these interval sets also imply many of the harmonies embedded within the 4-tonic system. In this context, it will be useful to think of the leading tone as both the note lying a semitone below any tonic and also as a raised fourth resolving to the fifth, also known as a double leading tone. That being considered, the pitch collection B-C-Eb can function as part of a C minor scale or an F minor scale (Fig. 12a). In Figure 12b, pitch collection Eb-E-G includes flatted-7th and raised 7th leading tones approaching F minor. F minor is strongly implied when the next note in the augmented scale, an Ab, is added to form the tetrachord Eb-E-G-Ab. The pitch set E-G-Ab (not shown below) also implies F minor. In Figure 12c, the pitch collection G-Ab-B can imply an Ab minor scale. When followed by a C—forming an (0145) tetrachord—it can imply another F minor chord (or a Dm7(b5)). The fact that F minor, in particular, can be so constistently implied is of great significance to bridging between systems.

Fig. 12a-c: Augmented scale sets can imply 4- tonic harmonies

Fig. 12a:

Fig 12b:

Fig 12c:

1.4 The gatekeeper: The flatted-6th as the structural link between 3- and 4- tonic systems

4-tonic systems, integral to bebop harmony, and 3-tonic systems, integral to more chromatic harmonies stemming from "Coltrane changes," share some embedded chords that can act as pathways from one tonal palette to the other. Examining these pathways is of import to creative development for practical reasons: the 4-tonic system, particularly because of its implied tri-tone II-V chord progression, serves as the primary harmonic focus for countless jazz musicians. 3-tonic systems, on the other hand, only tend to be explored when handling works by Coltrane, compositions that even then tend to be performed by only the bravest of players. Augmented scale theory, at the very least, can assist musicians as they move beyond digital patterns and other less than creative approaches when working with 3-tonic systems, helping their improvisations move from tired to inspired.

The flatted-6th serves as a pivotal pitch in 3- and 4- tonic systems. In the key of C, Ab minor is of significance to both systems, functioning as one of the three minor chord pillars of the 3-tonic system and as the tri-tone substitution of the II chord within the 4-tonic system. Ab major is equally important. It functions as one of the major tonics of the 3-tonic system, and it is the relative major of an F minor chord, which functions as the minor third substitution of the II chord in the 4-tonic system (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13: Ab major: The link and passageway from a 3-tonic system to a 4-tonic system

The link between 3- and 4- tonic systems can also be viewed geometrically (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14: 4-tonic square and 3-tonic triangle, linked in the key of C by F minor/Ab major

1.5 Establishing a chromatic hierarchy: Interval sets unite common chords

Interval sets are structurally significant to augmented scale theory, not only because (013) and (014) trichords form the basis for 3- and 4-tonic systems, but also because they can be used effectively in practical application to unite harmonies possessing varying levels of tension. Scales and modes, by design, are also built from interval sets, and, on one level, sets represent a convenient way of labeling any small melodic or harmonic fragment. Whether sets and intervallic improvisation remain integral to the composer or improviser is up to the musician, who might prefer to develop harmony and melody by exchanging the terminology of sets with a similar concept of scale fragments.

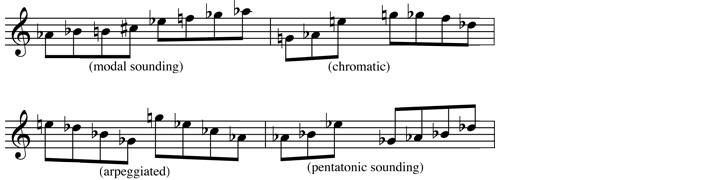

Scale fragments date back to the Greater Perfect System, the ancient Greek root of Western harmony, which was built upon the concept of tetrachords.[9] The D Dorian minor scale, for example, is built upon two like tetrachords separated by a whole step: D-E-F-G, A-B-C-D. This is significant for improvisers and composers alike, who often choose to explore only a portion of a scale before moving to another scale entirely. A small collection of pitches often forms a scale fragment that belongs to more than one scale. For instance, the pitch collection D-E-F forms an (013) trichord, and it also represents a fragment from scales belonging to D minor, G dorian minor, E7(b9) and several other scales and chords. Whether viewed as interval sets or scale fragments, augmented scale theory maintains a view that all pitch collections hold a hierarchical placement in the chromatic spectrum, governed by the gravity of both underlying and implied harmonies. For instance, in the key of C, Ab major and Ab minor are structural chords in the augmented scale theory hierarchy. In the example below (Fig. 15), the chromatic chords C# minor, Eb minor, and Bb minor, can be viewed as belonging to Ab major and Ab minor through shared scale fragments or interval sets.

Fig. 15: Common interval sets unite C#min, Ebmin, & Bbmin with hierarchical chords AbMaj and Abmin.

(These sample 3 and 4 note sets can be heard as relating to any of the above chords.)

(Fig. 15):

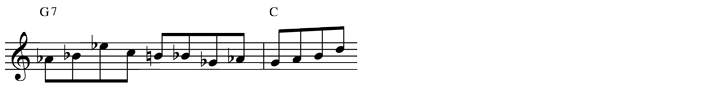

What matters is not what exact scale or mode is used—for instance, whether, over a G7 chord, a musician plays Bb minor or F minor (both of which stem from augmented scale theory's structural Ab harmony—but, rather, how each note relates to the chord tones that surround it. In his book, "A Chromatic Approach to Jazz Harmony and Melody," Liebman analyzes the first two beats of the line below as a Bbmin7 over a G7 chord, but it just as accurately could be analyzed as an Fmin7 superimposition (Fig. 16).[10]

Fig. 16: The first four notes of this line outline Bbmin7 or Fmin7

Because of the tendency for F and Ab to resolve to E and G, respectively, the F minor chord also takes on characteristics of a dominant G7 chord. Whether a musician, when playing a line over G7 (key of C) (Fig. 17), thinks of his line as stemming from an F Lydian diminished scale, or, perhaps, an F Dorian minor scale with a double leading tone, has far less musical relevance than how the particular scale fragments resolve (or relate) to given and implied harmonies.

Fig. 17: This line could be derived from F Lyd. dim., F Dorian minor (with leading tones), or G mixolydian (add b9).

In the key of C, the C augmented scale, or "tonic augmented scale," proves to support chromatic harmonies involving a generally altered dominant sound palette, and as this palette is so ubiquitous in jazz, the scale serves a broad purpose. However, by limiting augmented scale theory to only one augmented scale, several notes significant to jazz—including (in the key of C) D, F, A, and Bb—can only be implied pitches, as they do not belong to the original augmented scale. This fact necessitates the introduction of other augmented scales.

PART TWO — Using four augmented scales to build the chromatic spectrum

2.1 The chromatic palette: Tonic, subdominant, dominant, and subtonic augmented scales

Once the subdominant augmented scale (based on F, assuming the key of C), the dominant augmented scale (based on G) and the subtonic augmented scale (based on Bb) are introduced into augmented scale theory, all pitches critical to chromatic and tonal harmony can be addressed and examined without relying on any implied notes. The connections between chords become so vast that any interval set can be justified when played over the tonic key. The goal of systematizing a freely chromatic concept of "any note, any time, anywhere" has been reached, and, significantly, at any moment a return to a tonal sound palette can be achieved with much greater ease. In Figures 18a-c, subdominant (F), dominant (G), and subtonic (Bb) augmented scales have been illustrated, highlighting the scales' defining chords.

Fig. 18a: Subdominant augmented scale (highlighting F major) (key of C)

Fig. 18b: Dominant augmented scale (highlighting G major) (key of C)

Fig. 18c: Subtonic augmented scale (highlighting Bb major) (key of C)

Figure 19 includes a collection of tonic, subdominant, and dominant augmented scales in the key of C. This ordering helps illustrate how each chromatic pitch in these scales exhibits a tendency to resolve up or down to neighboring chord tones.

Fig. 19: Combined tonic, subdominant and dominant augmented scales

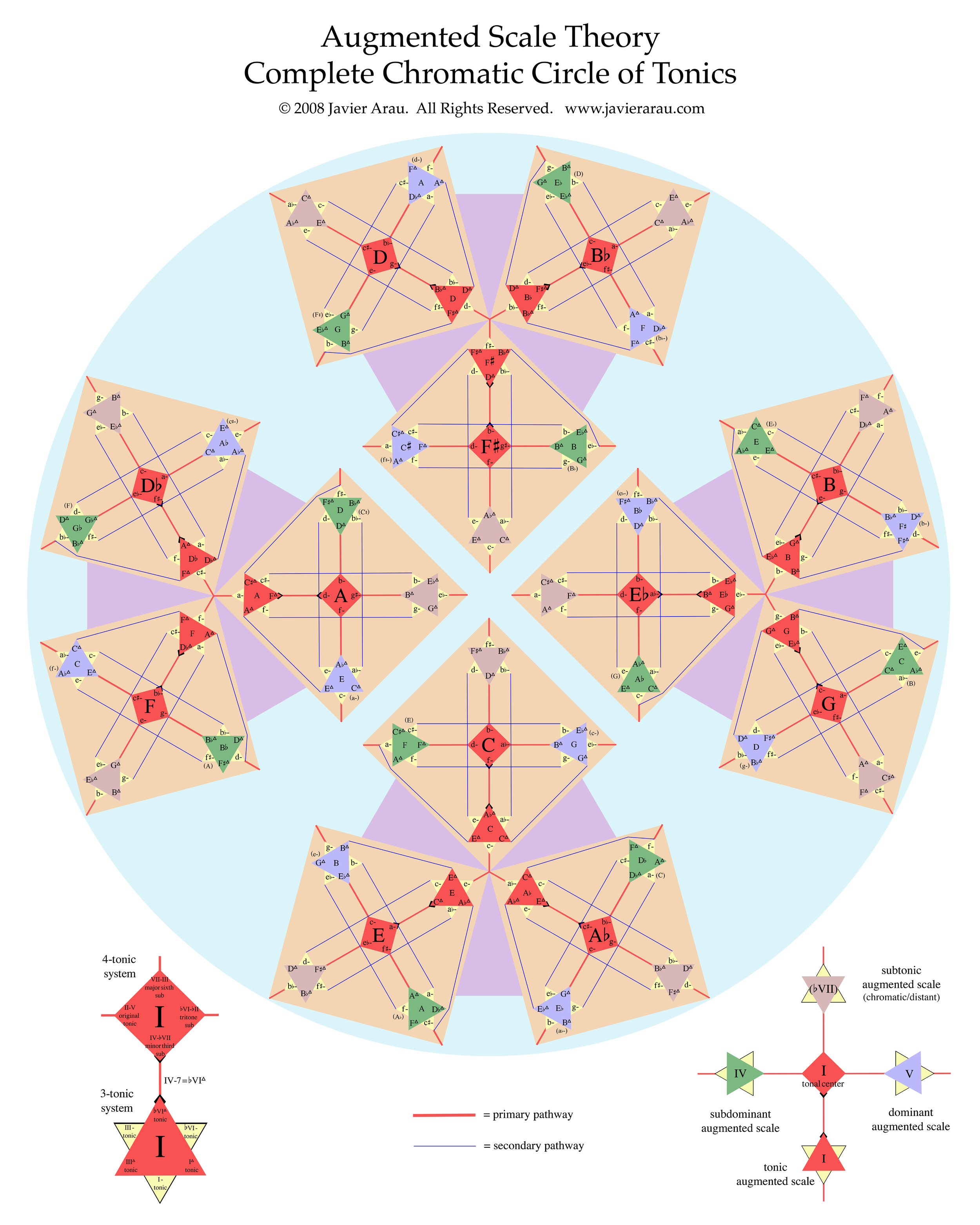

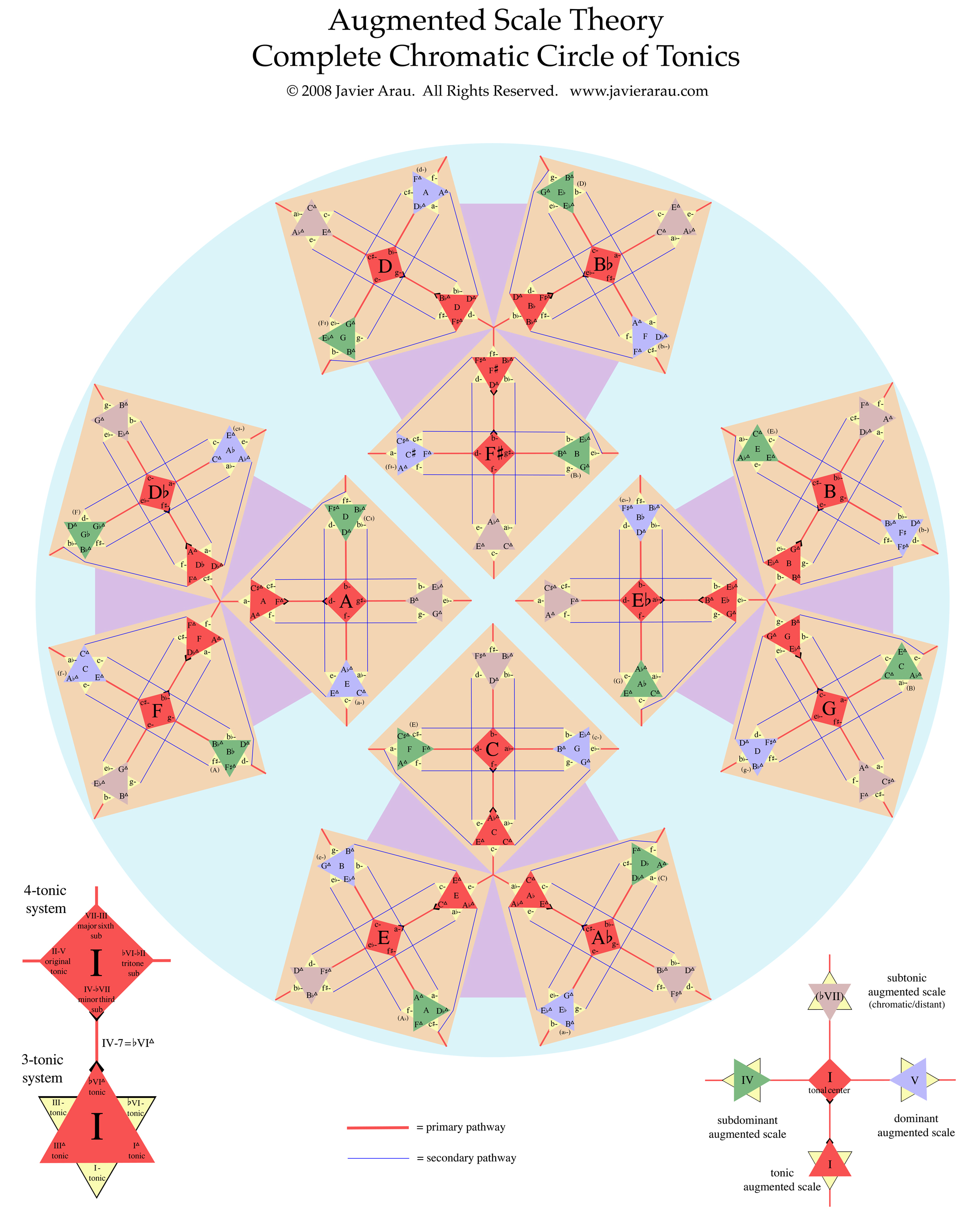

2.2 The big picture: The geometry of augmented scale theory

What follows is a series of geometrical illustrations that helps to highlight the logic behind the four augmented scales and how they relate to a corresponding 4-tonic system. The geometry of augmented scale theory contains fractal properties; each illustration functions as a structural component of the illustration that follows. There are too many threads connecting the harmonies in these illustrations to begin to address them at length in this paper, although a few of the most significant connections in each illustration are labeled as primary or secondary pathways. Note that the II-V progressions at the corners of each 4-tonic system are represented only by their corresponding II chords. The V chords have been omitted because they were implied by the existing II chords and thus were deemed redundant.

Figure 20 introduces all four augmented scales and illustrates how they relate to a central tonic. All four augmented scales are structurally integral to augmented scale theory's complete chromatic palette, as evidenced by the geometry in the examples below, but, of the four scales, the subtonic augmented scale is the most chromatic and tonally distant in relation to the central tonic. It is no coincidence that it forms a primary passageway with the most distant and impractical of the 4-tonic system's II-V chord sets, the major 6th II-V substitution. Subdominant and dominant harmonies have more structural significance than subtonic harmony in tonal theory. This holds true with augmented scale theory, as well.

Fig. 20: 3-tonic square, annotated

Fig. 21: 3-tonic branch (detail of Complete Chromatic Circle of Tonics)

Note: The central tonic (red triangles and red squares) of each 3-tonic square extends out from the center of this 3-tonic branch.

Fig. 22: Augmented scale theory's Complete Chromatic Circle of Tonics

CONCLUSION

Augmented scale theory holds broad implications for use in musical analysis, but, perhaps more importantly, it is meant also for practical application, helping to ease the steep learning curve that improvisers and composers face in the quest to work with chromatic palettes. A significant advantage to using augmented scale theory is that it distills harmony down to its essential function of tension-release. With this simplification, the musician need not become entangled in long lists of scale options for every chord and can instead dedicate more effort toward controlling a tonal (or atonal) landscape. In addition, when working with the augmented scale as a central tonal structure, the jazz musician can more quickly develop fluency in multiple key centers. Instead of working toward mastery of 12 independent keys, the musician can trim the amount of work down to developing fluency within 4 independent tonic augmented scales.

This paper serves only as a brief introduction to the topic of augmented scale theory. The focus here has been more on jazz line and improvisation than on composition. A more exhaustive study on the topic must include a careful examination of practical applications in improvisation and composition—including the use of wider interval sets and common pentatonic and octatonic scales—and an extensive analysis of historical examples of chromatics and interval sets in jazz, as viewed through this lens.

ENDNOTES

- David Liebman, "A Chromatic Approach to Jazz Harmony and Melody." (Rottenburg, Germany: Advance, 1991) « return

- George Garzone, personal interview, Sept. 1998. « return

- Liebman, 25. « return

- Liebman, 14. « return

- This is only an observation and is not intended to be a value judgment made towards the artist making such a choice. « return

- In set theory, the twelve chromatic pitches are each assigned a number, beginning with zero (0). These numbers then help generate pitch sets which allow for quick and easy modulation and development and can help give the work an organic structure. The sets are numbered from smallest interval to largest, regardless of their order. Thus, the pitch set C-Eb-E is considered an (014) trichord, not an (034). For a more involved introduction to set theory, consult Allen Forte's "The Structure of Atonal Music" or a similar text. « return

- Liebman argues that every II-V superimposition has a unique tension-release relationship to the prevailing tonic, dependent largely upon how many common tones the superimposed chord shares with the original. The II-V minor third substitution exhibits a particularly low scale of dissonance because it shares several common tones with the original II-V (p. 19). « return

- The fourth tonic, A major, often becomes more practical when changed to A minor, thus becoming the relative minor of a C tonic. « return

- "Greece," The New Harvard Dictionary of Music, 1986. « return

- Liebman, 21. « return

REFERENCES

Bergonzi, J. (2003). Inside improvisation series, Volume six: Developing a jazz language. Rottenburg, Germany: Advance Music.

Coker, J., Casale, J., Campbell, G., and Greene, J. (1970). Patterns for jazz. Miami: Studio Publications.

Forte, A. (1973/1977). The structure of atonal music. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Levine, M. (1995). The jazz theory book. Petaluma, CA: Sher Music Co.

Liebman, D. (1991). A chromatic approach to jazz harmony and melody. Rottenburg: Advance Music.

Randel, D. (Ed.). (1986). The new Harvard dictionary of music. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Russell, G. (2001). Lydian chromatic concept of tonal organization, Volume one: The art and science of tonal gravity. (4th ed.). Brookline, MA: Concept Publishing.

Weiskopf, W. and Ricker, R. (1991). Coltrane: A player's guide to his harmony. Indiana: Aebersold.